This is the fourth article in a series on the transfer experiences of North Carolina’s students between community colleges and four-year institutions. Click here to read the rest of the series.

Forsyth Technical Community College expanded Bailey Artz’s expectations for what he was going to get out of a college education. And that changed his life, he said.

Artz will finish his Associate of Applied Science (AAS) degree in diesel and heavy equipment this spring. He is going right back to Forsyth Tech this fall for a program where he’ll earn his associate degree in horticulture then transfer to North Carolina A&T State University to get a bachelor’s in agricultural education, which is designed to take two years at each school.

Artz is going to get a job using his diesel degree, he says, and work his way through his associate and bachelor degrees to supplement his Pell Grant and additional loans. The first degree Artz will earn will help him pay for the next two — a positive feedback loop when it comes to the value of education.

By the time he graduates, Artz will have been in school for six years, assuming all goes according to plan. Artz, a high-achieving student with support at school and at home, has a good chance of making it through.

The first choice

When students enroll at a community college, they have a choice to make. Do they want to pursue a degree they can apply toward transfer to a four-year institution, like an Associate of Arts (AA) or Associate of Sciences (AS), or do they want to get a workforce certification?

Sometimes, as in Artz’s case, students pick the workforce track, but then get a taste of education that works for them — and, suddenly, their entire trajectory changes. Artz has some advice for people considering community college.

“Research,” Artz said. “Research everything you know you want to do and all the classes you need to get your degree.”

He did not do that, he said, in part because he was not planning on transferring or getting a bachelor’s degree when he started at Forsyth Tech.

When students like Artz — students with a workforce or technical degree not designed for transfer, like an AAS — pursue bachelor’s degrees, they tend to collect a lot of excess credits because their courses often do not count toward their major at the university.

In North Carolina, this group of students is only growing.

Bringing “other associate degree” students under the transfer umbrella

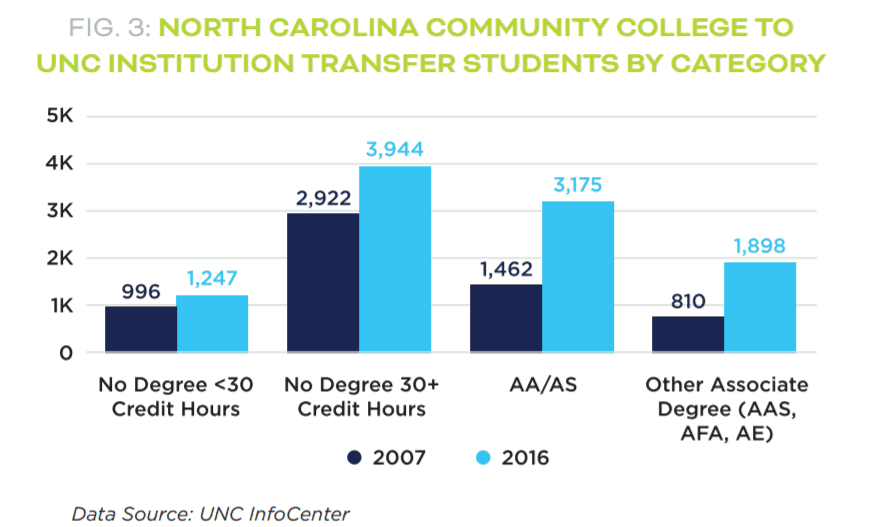

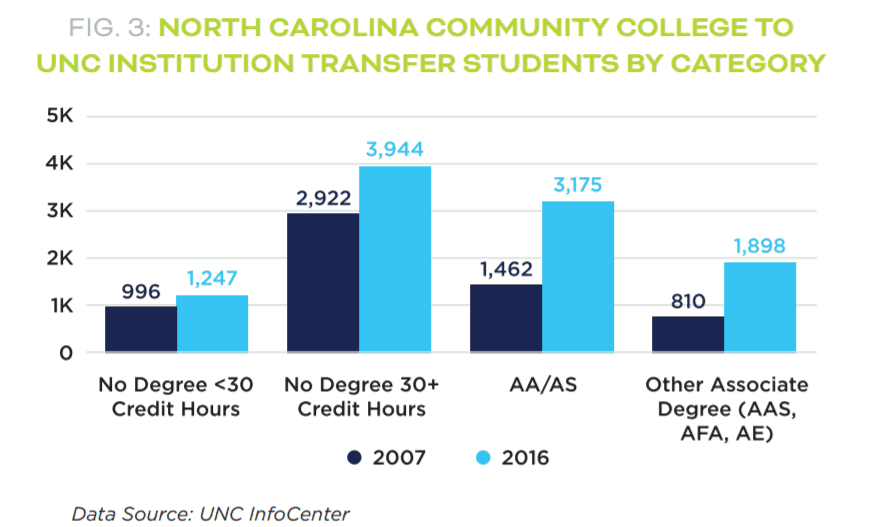

“Other associate degree” students (that’s other than those getting an AA or AS) are the fastest-growing group of transfer students. Between 2007 and 2016, the number of transfer students with a non-transfer degree grew by 134%. They now make up 18% of community college transfers.

A higher ratio of students from more economically distressed areas transfer with applied science degrees, according to University of North Carolina at Charlotte professor Mark D’Amico. What’s more, AAS students are earning important workforce degrees, D’Amico said.

This is backed up by data from the Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research. Their numbers show that 60% of applied science transfer students who graduated with a bachelor’s earned their degrees in either STEM or health, the two largest and fastest-growing sectors of the state’s economy.

But because applied science degrees are not “transfer degrees” historically, they are not protected under the statewide transfer rules created in 1997 and updated in 2014. The Comprehensive Articulation Agreement (CAA) lays out rules for transfer between the state’s 58 community colleges and 16 public state universities. A similar agreement was passed with 30 of the state’s private colleges.

Under the agreement, Associate of Arts and Associate of Science degree-holders have guaranteed admission to a UNC System school and have their general education requirements waived.

Including Associate of Applied Science students under this umbrella to help them “continue toward a baccalaureate degree more seamlessly would make a lot of sense for North Carolina,” D’Amico said.

Promising practices

Based on his 25 years of experience working with community colleges, D’Amico said North Carolina has a strong tradition of working to improve transfer.

“I see a constant commitment to strengthening opportunities for transfer students,” D’Amico said. “Quite frankly, right now, I do see even greater momentum with some of the statewide efforts like myFutureNC. I see really strong partners over there trying to work it out.”

Three frameworks already exist that could help community college and public universities better incorporate applied science students into the CAA and improve their transfer prospects.

The first is a set of courses guaranteed to transfer for general education credits, the second are statewide transfer agreements for specific associate degrees, and the third are agreements between individual community colleges and four-year colleges.

The guaranteed transfer courses are covered by the Universal General Education Transfer Component, commonly known as the UGETC. The idea is simple: if you get a “C” in any of the UGETC courses, that credit is guaranteed to transfer to a public university in North Carolina under the 2014 agreement.

UGETC courses are used to guarantee that students who transfer before they earn an associate degree still have some guarantee that credits earned at the community college will be applied toward a bachelor’s. They also provide structure for dual-enrolled students who are trying to collect college credits while still in high school. UGETC courses generally translate to general education course credits.

But UGETCs are providing an opportunity for applied science students, too, according to Wesley Beddard, the associate vice president of programs at the North Carolina Community College System.

“Almost all [community colleges] now are going in and re-looking at their GenEds to allow students to take transfer courses that meet both the AAS and transfer,” Beddard said.

This is allowing a reorienting of applied science tracks in community colleges across the state, Beddard said, especially for high-frequency transfer programs like business administration, criminal justice, and early childhood education.

In retrospect, Artz could have taken UGETC classes, he said. But he did not know about them and, as a student who did not indicate he was interested in transferring when he enrolled, he was not advised to.

Seeking a degree outside of the most common transfer tracks also complicates Artz’s pathway. To meet high demand, the community college and public university systems have established transfer pathways for a few high-frequency or specialized degrees.

These “Uniform Articulation Agreements” are the second framework that can be built upon to benefit Associate of Applied Science students. They cover associate degrees in early childhood, engineering, fine arts, and nursing.

Most community college degrees, though, do not have statewide transfer pathways. Instead, community colleges and university partners build their own individualized pathways. There are more than 100 of these “bilateral articulation agreements,” many of which specifically address transfer with an AAS degree, D’Amico said.

These represent the third framework from which more protections and better transfer pathways for applied science students can be built. Working with these local partnerships could be a good place to start creating more opportunities which could later earn statewide implementation.

D’Amico cites research saying the North Carolina system is “institution-driven.” This means that, even though there are statewide agreements on transfer, the details around transferring credits and seeking specific degrees are mostly hashed out between individual schools.

That could be one of the reasons transfer students are most commonly successful when they transfer to a four-year college within the same county as the community college they attended. Community colleges are more likely to know the ins and outs of the requirements for each major — called baccalaureate degree plans — at their nearby universities.

“I think in most cases, it’s going to be easiest for students attending a local community college and transferring to a local university,” D’Amico said. “It’s going to be seamless, it’s going to be easier for them to follow the destination or receiving university’s baccalaureate degree plans, and it’s going to then be easier for advisors to advise them on a familiar curriculum.”

Improving transfers

A new report from the Belk Center for Community College Leadership and Research says, “the CAA does not focus support on students who can earn Applied Associate of Science (AAS) degrees even though the rate of transfer among this students population has increased dramatically in recent years.”

A policy brief prepared for myFutureNC by Mark D’Amico, a professor at UNC-Charlotte, and Lisa Chapman, then chief academic officer for the NC Community College System and now president of Central Carolina Community College, offers these considerations to the state:

North Carolina does not currently maintain a repository of information about [bilateral articulation] agreements. There is an enormous opportunity to share information about these agreements to assist A.A.S. students in making an informed choice about baccalaureate options. Kujawa (2013) showed that the mere presence of an applied baccalaureate (the type of program to which an A.A.S. may articulate) at a four-year institution “heated up” community college student aspirations. Incorporating universally transferable UGETC courses into A.A.S. degrees—thus guaranteeing the smooth transfer of at least half of the associate degree—could add to that heat. Cataloging existing agreements and incorporating transfer courses into applied programs should encourage completion, potentially expand transfer enrollment, and present options for other universities, public and private, to adopt similar agreements.

Behind the Story

Reporting for this article was primarily conducted by Jordan Wilkie.

This article was edited by Molly Osborne, Eric Frederick, and Mebane Rash.