FIRST STEP TO THE MIDDLE CLASS: More than 27 million Americans age 25 or older don’t have a high school diploma or GED, the basic credential needed to qualify for nearly 80 percent of jobs in this country. The Hechinger Report traveled to three counties with very high numbers of adults without a high school credential to learn about the obstacles schools and families must overcome to provide and obtain this essential first step to a middle-class life. The three counties, all in the rural South, are profoundly different in terms of race and ethnicity – and in their experiences of racism and segregation. Yet they face many of the same challenges, including low funding for schools, intergenerational poverty and few well-paid career opportunities to motivate students. They also share one abiding theme: Parents know the risk of dropping out of school and want desperately for their children to get through high school and beyond in their education.

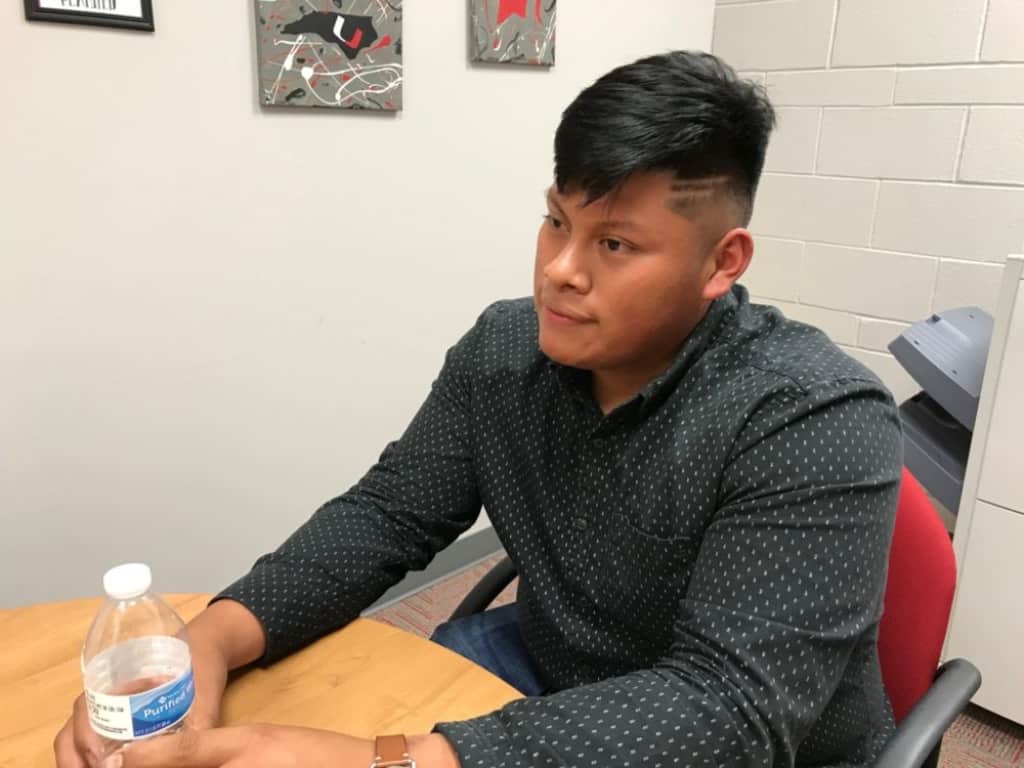

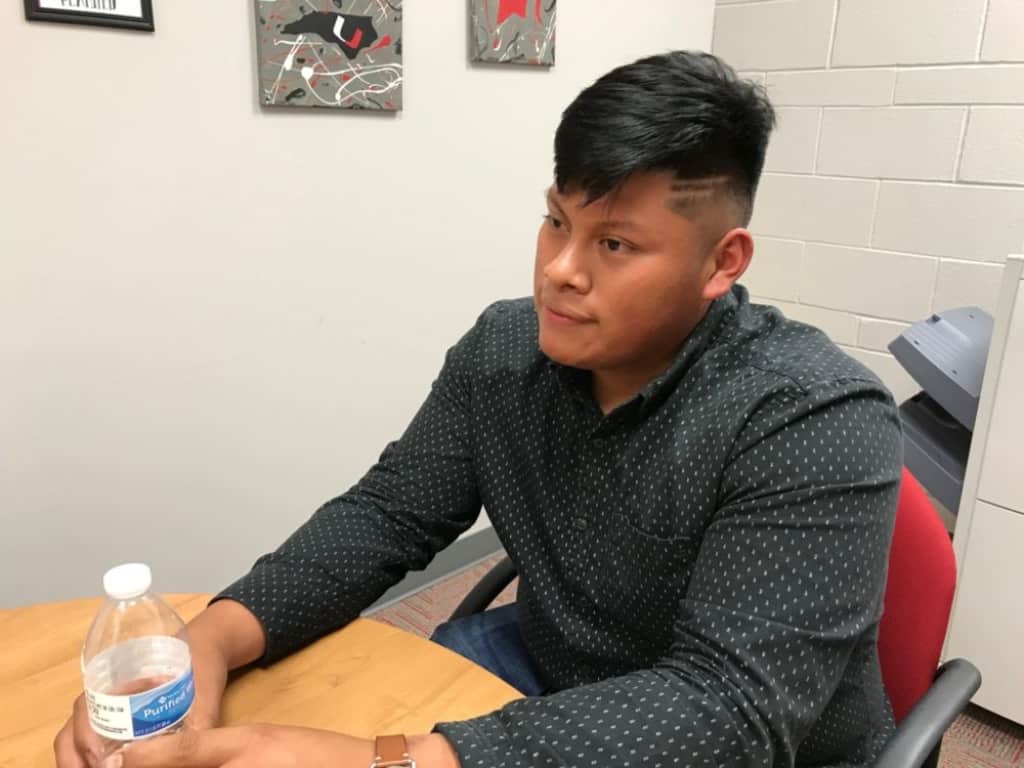

ROSE HILL, N.C. — Last summer, Mayko Calmo-Gomez spent most days picking tomatoes. The plastic walls of the greenhouse he worked in trapped the heat and humidity, and the air felt almost solid. He kept a bandana over his face to limit the chemicals he inhaled and make breathing easier. Within the first hour of those 12-hour days, his shirt would be drenched, sticking to his skin as he stooped and shuffled through the narrow pathways between the plants.

Mayko, now 19, has spent most of his summers since middle school working with his father in the fields and greenhouses of this rural county in central North Carolina. His sisters worked in warehouses, everyone chipping in to pay the bills and rent for their double-wide trailer home. The family needed every hour of work they could get.

Six years ago, his mom left for a job interview, a position that offered more money than she could earn working in hotels and factories. But there was a car accident, and she never returned, leaving behind Mayko, who was 13 at the time, and his three siblings, who were 11 months, 9 years and 12 years old.

After his mother died, Mayko’s world was shattered, and his perspective shifted with the tumult. He went to work to help his dad support his siblings, but he also remembered his mom’s insistence that he study. It had been constant. Neither she nor his father, who emigrated from Guatemala in 1993, had finished middle school.

The teenager devised a plan to pull his family out of poverty and his father out of the fields. After work every day, he set aside time for homework, even if that meant sleeping fewer hours than his body wanted. He went online searching for careers that paid well and required math, in which he excels.

“My dad was always telling us we needed to get an education,” said Mayko. “Me being the oldest, I have to set a role model for my younger siblings. My dad tells them, I tell them, ‘just don’t give up.’”

Mayko is among a new generation of Latino students in Sampson County who are striving for something that eluded their parents. The county is known for hogs and blueberries, which provide jobs that have attracted hundreds of Latino immigrant families. The percentage of Latino students in the county has grown from 27 to 40 percent in the last decade. But the jobs have a downside. The work is hard, the hours are long and the pay is meager, exacerbating a cycle of poverty that has been tough to break. Just 31 percent of Latino adults who are older than 25 have a high school diploma, one of the lowest rates in the country.

Without a high school diploma or GED, it will be next to impossible to find a decent job in the coming decades, but 27 million American adults are in this predicament, without the basic level of education they need to reach the middle class. It’s a particular problem for immigrants from Mexico and Central America, who drop out of high school at much higher rates than their native-born peers.

Part of the disparity starts in home countries where access to education is often limited. High school graduation rates in Mexico have improved over the last decade, but 52 percent of 25- to 34-year-olds lack a high school education.

In Guatemala and El Salvador, around a quarter of students don’t even make it through elementary school, according to the World Bank, while in Honduras, about 17 percent of children don’t get past primary school. For many immigrants, seeking something better for their children is one reason they come to the U.S. But the financial need for all family members to work can undermine their goals. Adults coming from Central America and Mexico often end up in low-wage jobs due to immigration status, discrimination and a lack of formal education.

For students who aren’t fluent in English, some state policies put them at a further disadvantage. Georgia, Arkansas and Florida, for example, have English-only laws, which prohibit teaching in Spanish. And 32 states, including North Carolina, don’t require English language learner training beyond the minimal federal requirements for general classroom teachers. Districts around the country also face a shortage of bilingual and ESL teachers.

27 percent of Latino adults who are older than 25 in Sampson County, N.C., have a high school diploma, one of the lowest rates in the country.

Sampson County’s challenges exemplify the barriers many Latino students face making it to graduation, but the county has found ways to chip away at those obstacles. High school graduation rates here have been rising. Seventy-nine percent of Latino students graduated from Sampson County schools last year, up 3 percentage points from 2014 and just about matching the state average.

But significant obstacles remain. At Union High School, where Mayko was a student, only 21 percent of incoming ninth graders could do math or read at grade level in 2017.

The district is among the lowest in North Carolina in per-pupil spending, at $9,263 in 2018, and the state is already one of the lowest in the country in per-pupil spending. Tight budgets keep teachers’ salaries depressed, which has made hiring tough, and the schools have had to cut corners in the classrooms — sometimes there aren’t even enough textbooks to go around. ESL teachers have to travel back and forth between middle and high schools, because there aren’t enough for each school in the county to have their own. The county’s ability to raise local funds for the schools to supplement the state money it receives is minimal — it’s 96th among 100 counties in property values, according to an analysis by the Public School Forum of North Carolina.

And 42 percent of the county’s Latino residents live in poverty — more than twice the rate of white residents.

Many Latino adults work in the fields, and those jobs, for which wages are often based on how many boxes of blueberries or crates of sweet potatoes workers can fill, disappear when the harvesting season ends. For families to survive, the children have to help out; they can work in the fields starting at age 12. The long hours that some high school students work, on weekends and after school, in the fields or in restaurants, can clash with homework demands.

“There are times when my kids are working until one, two, three in the morning picking blueberries,” said Julie Hunter, who is principal at the nearly 500-student Union High School. “I called the businesses and told them, ‘You gotta let these kids go home at 10 p.m.’ They get to school and they’re exhausted.”

The Trump administration’s recent immigration raids and the ongoing threats of additional ones have created more problems, as fear of deportation ripples through the county, keeping parents away from government institutions like schools and at times creating crippling anxiety for their children.

Earlier this spring, immigration enforcement officials arrived in Newton Grove, a town several miles north of Union High School, and started making arrests.

“The school was in a panic,” said Kendric Faison, who is the student support specialist at Union.

Among other things, Faison is in charge of finding students who are chronically absent. He calls and visits families at home in an effort to boost attendance. Sometimes he arrives at a trailer home to find it abandoned, the migrant family having moved on to states further south where there is still work in the fields. They leave for the winter and return in the spring. When the children re-enroll at Sampson schools in May, in time for blueberry season, they are expected to pass North Carolina’s state tests after having been gone for months.

“When a kid drops out, the biggest thing is work,” Faison added. “Sometimes the family just doesn’t know that getting a high school diploma can open doors. Sometimes they’re scared about deportation and about their kids coming to school.”

Narivi Roblero-Escalante, 19, used to travel with her family, following the crops with the seasons. Her parents, who emigrated from Guatemala in 2000, were among those who never made it through elementary school. That fact motivated her to stay in school, but so did an incident when she was a sophomore at Union High.

She was sitting next to her friend Lorena in class, behind two white girls who were discussing the best students in their grade. Narivi had just arrived that year at the school, which sits miles from the nearest store and is flanked by fields that stretch to the horizon. At that time, she didn’t know what a class ranking was, but as she listened, it became clear. One of the girls, who was ranked second in the class, told her friend, who was first, that there were no Hispanics in the top ten students in their grade.

“I remember that my friend Lorena got very upset,” recalled Narivi, taking a break from the fields during a 90-degree afternoon in May. “Lorena and I, ever since then, it was our mission, I guess you could say, to reach those spots, to be number one and two.”

She thought about their pact sometimes when she was picking sweet potatoes and berries with her parents in Sampson County. In the summer they traveled to Michigan or New Jersey where the workdays stretched from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m.

“I knew I didn’t want that for myself, in the future. I didn’t want that in the future for my parents, too, and I knew if I was going to help them out, I had to go beyond what I would normally do,” said Narivi, who came to the United States when she was just a few months old. She is a recipient of Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, a status that protects her from deportation.

“I’m also undocumented, so I had to try even harder to make up for that and try and find another job to support me and my family in the future,” she said.

The summer before senior year, even though school was out and she still needed to pick all day, she kept studying, sometimes working late into the night. She finished one high school course and two online college courses that summer.

It paid off. Narivi graduated in 2018, as valedictorian, and got a full ride to the University of North Carolina. She is now a sophomore. Her friend Lorena was salutatorian at Union.

Race and ethnicity play a complicated and evolving role in educational outcomes in the county. Like Latinos, African Americans historically have had less access to quality education. The situation has improved markedly for black residents in Sampson County, but there are still some significant gaps.

Last year in Sampson County, black students had higher graduation rates than Latinos at all four traditional high schools. At the same time, they were much less likely to have taken an Advanced Placement course than Latinos or whites. Black students also tended to score lower on state math tests and do worse on ACT exams than Latinos or whites, even at the high schools where they graduated at higher rates than either group.

The Hechinger Report wants your questions. You ask. They answer.

African Americans are underrepresented at the district’s small early college high school, which enrolls about 250 students, over half of whom are Latino, with a more than 95 percent graduation rate.

Union High School, where Narivi went, is 43 percent Latino and serves many of the district’s migrant children. The school graduated 72 percent of its Latino students last year, surpassing the 69 percent graduation rate of white students.

The racial graduation gap between Latino and white students at Hobbton and Midway High Schools is still significant — 10 percentage points — but graduation rates for Latino students at both schools rose by about 7 percentage points over four years.

Jennifer Daughtry, who became principal at Hobbton in 2013, said the key to her school’s improvement was forging closer relationships with students and their families.

“It’s just basically getting to know your students,” said Daughtry, who was tapped to oversee all five of the district’s high schools in January. “If I had students who had situations at home, and I knew they were missing class, I just said ‘Okay, what can I do to keep you in school?’ Some of them had to stay home to keep their siblings while their parents worked. I would get them a computer and let them take those classes at home.”

In some cases, her students needed to travel with their parents to Mexico or other parts of the country because of family issues. She had teachers give them assignments for whatever period of time they would be gone and then made time in school where they could ask teachers questions and catch up on their work.

Daughtry and her team also began using data to find kids at the 500-student school who were on the cusp of dropping out. She met regularly with her guidance counselor and student support specialist to figure out a plan for those students, using credit recovery, summer school, online courses and home visits to get them through.

The school added AP courses, sometimes using an online program if they didn’t have the teachers or enrollment wasn’t high enough to populate a full class.

“A lot of my Hispanic students took those AP classes,” said Daughtry, with a smile.

A program called Juntos, which means “together” and was developed in partnership with North Carolina State University, also helped create a sense of community among Latino students. The program held evening meetings for families in Spanish, with Latin American food, to help connect parents to the school. Through Juntos, students visited colleges and were introduced to the application process. Students said that just having a place to meet and talk about their shared challenges has inspired them to persevere.

The school was lacking in bilingual staff, but the few Spanish speakers they had — including an advisor funded by Duke University — were lifesavers, Daughtry said. She called them in to communicate with parents and newly arrived students who hadn’t yet learned English. Teachers modified lesson plans to help students not yet fluent in English, and she introduced a separate English as a Second Language class for students who needed more support.

Daughtry also mandated that all students apply to at least one or two community colleges and four-year colleges. She had speakers with different jobs come to the school and talk to the students about what credentials they would need to find employment in each field. The staff took students to job fairs.

Although more Latino students in Sampson County schools are succeeding as the schools provide pathways for students like Narivi and Lorena, there are still big gaps between Latino and white students, and improvement has been uneven.

Another of the county’s high schools, Lakewood High, has struggled to connect with and motivate Latino students. Only 64 percent of its Latino students graduated last year compared with 88 percent of white students. The 540-student school, where about 19 percent of the students are Latino, is one of the poorest in the district. Last year about a quarter of the teachers didn’t return. However, the school did meet the academic improvement goals set out by the state by raising its Latino students’ state test scores.

Daughtry said there are some issues the schools just can’t fix.

“With some not having citizenship, it’s like, ‘What good is an education gonna do me?’” said Daughtry, who graduated from Hobbton High School herself in 1983. “‘I can’t further it anymore, because I can’t get into college. I can make more money working, and a high school diploma isn’t going to do anything for me because I can’t go anywhere with it.’”

Yet many undocumented students want more than a high school diploma. Some hope to open their own restaurant or become hair stylists. Narivi is looking into computer programming. Mostly, they just don’t want to work in the fields.

Daughtry sometimes uses her own story to encourage her students to imagine a better future.

“I’ve done every job in this system besides working in the cafeteria,” said Daughtry, who began as a teacher’s assistant in 1985. “I worked summers as a custodian. I’ve been a secretary, a bus driver, a teacher, a career counselor, an assistant principal and a principal. I shared it with my children. I told them, ‘You can’t always start at the top, but you can work your way up.’”

Esmeralda Pascual, 18, earned her diploma from Hobbton High School this spring. She worked the fields with her uncle and aunt when she was 12. The past few summers she joined her mom and dad in a sweet potato packing plant, working on the assembly line holding open the 50-pound bags and picking out rotten potatoes. During the school year, she worked some weekends waiting tables at a local restaurant. She helped out with housework after school but also had time to focus on homework. The schedule was manageable, she said.

“I wanted it first of all because neither of my parents finished high school,” said Esmeralda, whose parents emigrated from Mexico about 20 years ago. “I wanted to make them proud and graduate on time and set an example for my little sister.”

Sampson County schools have been harnessing all of the resources they can find to get students like Esmeralda to graduation, Daughtry said, but like most staff, she believes all the schools in the district have been hurt by a lack of funds. There are only two social workers for all 18 schools in a district where families and students could use much more support. They can’t afford to hire a psychologist, so the district has to contract out to get diagnoses for some students with special needs.

For Mayko, the impact of poverty on his family — and especially on his father — weighed more heavily than either the work he did in the fields or the academic challenges at school.

“There have been times I’ve been depressed, that’s probably the hardest times. When my family doesn’t have enough money,” he said. “It happened earlier this year, my dad was going through some stuff, the bills came all at once. I didn’t like seeing him that way, and it just made me sad.”

He tried to keep the feelings to himself, not wanting them to affect anyone around him. But earlier this year he finally spoke with some of his teachers, he said.

“Doing that helped me get over my depression more quickly, because it was a very strong one,” he said. “I’ve also had talks with my pastor, and I’ve cried in front of them and I’ve prayed. I owe them a lot.”

Playing soccer — he can handle any position — also helped him find some optimism. In May, he slipped a black graduation robe over his white button-down shirt, black tie and black pants. He wore several cords around his neck, awarded to students with stellar academic records. There was one for his 4.2 GPA and another for his membership in the National Honor Society. When his name was called, he rose to get his diploma and walked across the stage at Hobbton High School into his father’s arms.

“Graduating is really like an honor,” Mayko said. “I’m proud of being who I am, carrying my dad’s blood and my mom, representing her even though she’s not here. Keeping her with me is something that’s very important to me.”

In January, Mayko will attend the University of North Carolina in Charlotte. He intends to graduate from its engineering program, leaving the fields behind and bringing his father with him.

Editor’s note: This story about Latino students was produced by The Hechinger Report, a nonprofit, independent news organization focused on inequality and innovation in education. Sign up for Hechinger’s newsletter.