This article is part of a series and ongoing reporting on Latinx communities in North Carolina. Click here to read more.

Perhaps the most drastic shift in Latinx higher education over the last decade is the growth of Hispanic-Serving Institutions (HSIs). Largely a reflection of the country’s changing demographics, the number of HSIs has nearly doubled in the last decade. If this is the first time you are learning about HSIs, it’s understandable. North Carolina does not house any HSIs. At least not yet.

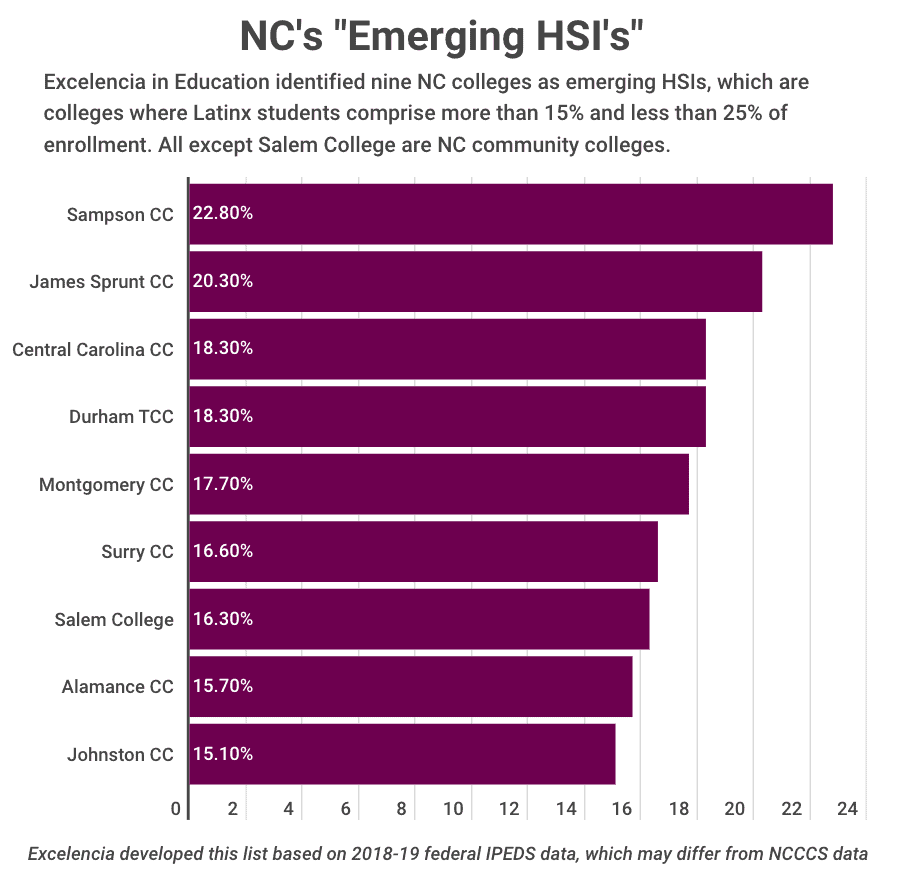

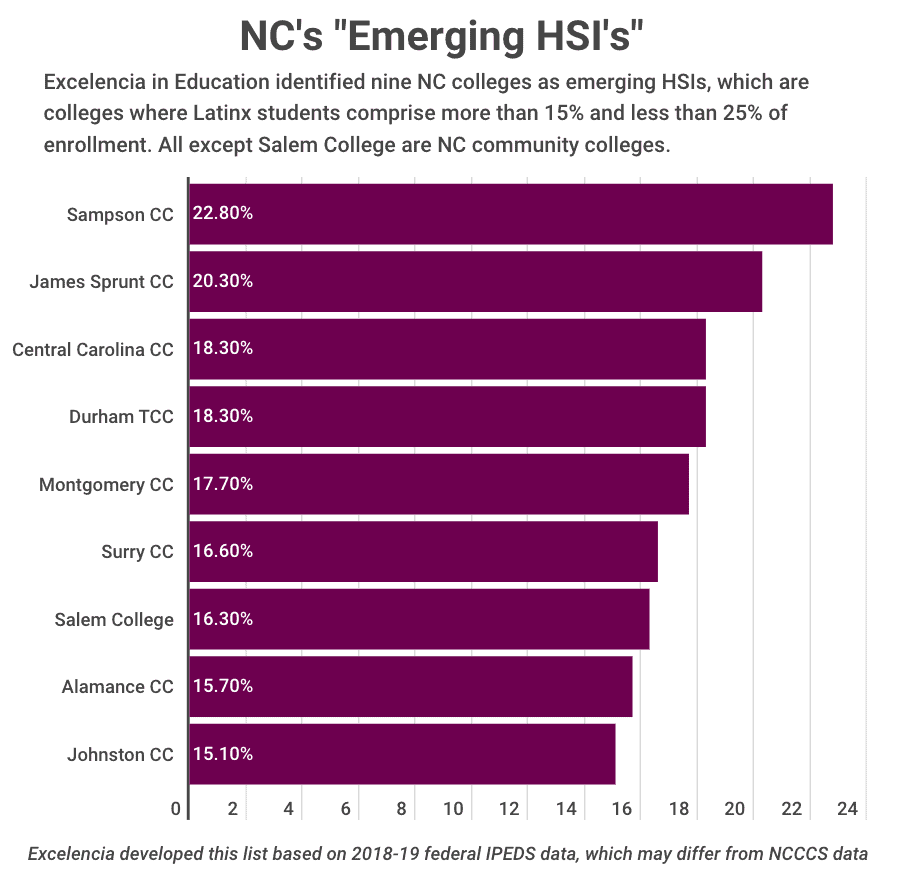

National advocacy group Excelencia in Education maintains a list of “emerging” HSIs — institutions that are right on the cusp of qualifying for the federal designation.1 For the first time in history, North Carolina made the list. In fact, nine colleges are quickly approaching the HSI threshold. The implications for North Carolina higher education, and community colleges in particular, speak to the opportunities and challenges ahead.

Striving for change in rural North Carolina

“My brothers said that when they were graduating high school, they weren’t sure they wanted to go to the workforce or the Air Force or to go to college,” says Esmeralda Lopez-Perez. “But since they went [to college], I knew I was going, too.”

Like roughly half of Latinx students nationally, Lopez-Perez and her brothers are the first in their family to attend college. Both brothers attended James Sprunt Community College, where Lopez-Perez is completing her associate degree. Their mom, who used to work in the fields, has been there every step of the way pushing her kids toward a college education. It is a generational shift that is both driving and reflecting changes to education systems, particularly in rural North Carolina.

Duplin County has seen significant change in Lopez-Perez’s lifetime. Since 2000, Duplin County has gained nearly 10,000 new residents, driven heavily by growth of its Latinx population, whose population share grew from 15% to 23% over that period. Over that time, the share of Latinx students in Duplin County public schools jumped from 13.7% to 42.5%.2

Lopez-Perez attended North Duplin Jr Sr High School, where Latinx students make up nearly half (48%) of enrollment, and 99% of students are free lunch eligible. Despite the high Latinx enrollment, Latinx students underperform compared to white students in proficiency and growth categories, and just 6% of English learners participate in AP courses. The school has reported more than four times the rate of behavioral issues as the rest of Duplin County schools.

But Lopez-Perez says this generation of Latinx students understands the significance of the opportunities beyond the challenges. “I’ve seen many people, throughout high school and in college, that want to do good for their family. Their family came here to give them a better life, so they don’t want to disappoint them. So they come and try their hardest,” she says.

An emerging HSI

James Sprunt Community College is on the front lines of meeting the demands of first-generation Latinx students. As more and more Duplin County students stay close to home for college, JSCC is on the cusp of gaining a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) designation in the next year or so. The designation itself is no guarantee of new financial resources, but it would make JSCC eligible to apply for grant programs that would help them better serve students like Lopez-Perez.

Unlike Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCUs) and Tribal Colleges and Universities (TCUs), which exist to serve specific ethnic minority communities, HSIs reflect the country’s fast-changing demographics. Any accredited public or private nonprofit institution with an undergraduate full-time equivalent enrollment of at least 25% Latinx students is eligible for federal recognition as an HSI.

Congress created HSIs in the 90’s as advocates and lawmakers recognized the looming need to develop education resources tailored for the Latinx population, which was in the midst of a 246% growth spurt.3 The first funds to HSIs were distributed in 1995, and three years later, Congress established Title V of the Higher Education Act specifically for HSIs.4

Becoming an HSI does not automatically come with new money. The Title V funding has become stretched thin over the last decade, and HSIs are merely eligible to first apply for formal federal designation and then compete for grants that support general Latinx student success initiatives and STEM programs. Only 40% of the country’s HSIs received federal Title V grants in 2019. Only 20% of the awards went to new HSIs, and the average of all awards was just $537,131.5 The prized funding comes in the form of five-year planning and program support grants.

Smaller community colleges like JSCC are well positioned to benefit and deploy such funds with a deep impact in their local communities. Some specific uses of the funds include community outreach to encourage young students to pursue higher education, enhancing success of transfer between two- and four-year institutions, and establishing or strengthening teacher education programs to qualify students to teach in public schools.

Those are the types of strategies that would help support more students like Lopez-Perez, who wants to be an elementary school teacher in Duplin County. After getting her associate, she plans to transfer to University of Mount Olive to complete a bachelor’s degree in elementary education. She thinks more engagement in primary and secondary schools would help get more Latinx students in and through college.

Beyond federal recognition

Jose Orellana moved to North Carolina from Honduras, where he finished high school. He knew college was likely in his future — his dad has a Ph.D. and teaches at a university in Honduras — but he needed somewhere to settle in and move into the college pipeline. He has found a home at JSCC.

“My life has been back and forth. I’d be going to Honduras, to Houston, to Charlotte. I mean, going to jump in schools my entire life,” says Orellana. He and his mom moved to Duplin County, where his uncle’s family lives, so Orellana could get his education in the U.S.

As a community college serving a heavily Latinx county, JSCC has been a good fit for Orellana to build a new community and develop his college career. Engaging with professors and students has been central to Orellana’s success.

“The most helpful thing is the people around me. If I have any questions — it can be that teachers or anyone at James Sprunt or even my family — I ask them questions and I basically have the answer like this is how I’m going to do it in the right way to do it,” says Orellana.

Intentional and targeted resources will be key to supporting a diverse array of Latinx students around the state. The sudden arrival of emerging HSIs in North Carolina tells a story of change in rural communities. The nine emerging HSIs are responsible for roughly 20% of the state’s Latinx students and live outside of the state’s major population centers.6 Seven of the nine emerging HSIs serve Tier 1 and 2 counties. The first colleges to cross the HSI threshold will likely be JSCC and Sampson Community College, which is right at the 25% mark after this year, according to recent NCCCS data.

“I think [HSI status] will affect students in high school by wanting to go to college knowing that they will have the support to go to one. Know that there are ways to get the money to be able to go to school. I also think that they will make the population of Hispanics going to school increase. More will not question whether they will go to school or not,” says Lopez-Perez.

Institutions like JSCC that are building community for Latinx students could make great use of federal funds, if the Title V awards ever become a reality. For now, the quick sprint toward HSI eligibility is a marker of the ways our counties are changing and the opportunities to strengthen programs that are doing the heavy lifting of securing Latinx student success.