This article is part of the Solution Seekers series. Find the full series here.

Brandi Bragg spent a year and $10,000 to get a medical assisting degree. “I worked that job for three months,” she said, when she realized she didn’t like touching people she didn’t know.

“My clinicals were in a lab with my classmates, who were people I knew, but it was a whole different ballgame out in the public,” she explained.

Bragg is now the Northeast North Carolina (NENC) Career Pathways facilitator, and she is working to make sure students don’t make the same mistake she did.

“If I had been out and I saw these people are coming in sweaty from work and I’m going to have to put this blood pressure cuff on them and I’m not going to be OK with that, I wouldn’t have done that. I would have done something different,” Bragg explained.

A partnership spanning 20 counties

NENC Career Pathways is a partnership that spans 20 counties and includes representatives from 27 local education agencies, nine community colleges, three universities, more than 100 employers, three workforce boards, 10 NCWorks Career Centers, and several community agencies.

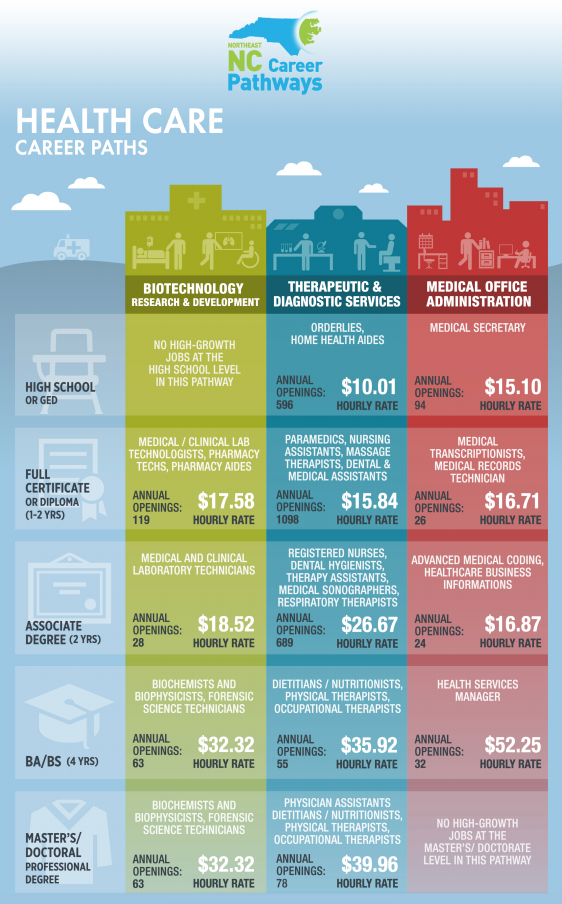

The goal is to identify and connect people to the various programs and services in the region to put them on the path to a career in a high-demand industry.

“Career pathways is about local and regional programs and services for education and training for youth and adults for highly skilled, sustainable wage jobs in high-demand industries,” Bragg said.

“If you don’t know what’s there, you can’t know how to prepare for it,” she continued. “And so that’s really what it is– just figuring out what’s there and helping connect it all and then making sure all the partners know about it.”

Lisa Lassiter is the administrator of Vidant Health Careers, where she works with the school systems to better align the skills students are learning with what they need to be successful at Vidant. She described career pathways as a GPS for careers.

“Really what it does is it gives them a tool that they can navigate to where it is they’re saying they want to be,” she explained, “or navigate far enough they find out that’s not really what they want to be doing. And then [it’s] able to still give them redirection to something else that’s pertinent to them.”

Careers pathways are necessary, she said, because often students don’t understand what different jobs are and how to get those jobs.

“We really need kids all the way back in sixth grade starting to make decisions about what it is they want to do and taking the appropriate coursework to go forward with that,” she explained. “And then there’s lots of credentials that you can tack on top as you go through those different courses … If you actually look at the pathway, it walks you through that.”

The pathways are helpful for parents too, Lassiter said, because both education and jobs have changed so much. If parents have never been to college or had experience in a specific sector, they won’t know how to guide their child, she said.

Pathways to Prosperity

NENC Career Pathways grew out of a 2011 report, called Pathways to Prosperity, from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education.

The Pathways to Prosperity report argued that the U.S. education system had placed too much emphasis on getting a four-year degree. With just 30% of young adults actually completing a bachelor’s degree by their mid-20’s, the authors argued that students needed multiple pathways to successful careers.

“It is long past time that we broaden the range of high-quality pathways that we offer to our young people, beginning in high school,” the report states.

Specifically, the report makes the case for clearly delineated pathways for all major occupations that outline the courses and experiences needed, starting in high school, to be successful in each field.

In July 2012, the Career and Technical Education Division of the Department of Public Instruction (DPI) developed a pilot project modeled after this report. DPI selected four school districts — Halifax, Beaufort, Martin, and Washington — to participate in the pilot.

These four soon grew to 20 as they decided to take a regional approach and include all the districts in the northeast region. From there, the partnership grew to include workforce boards, charter schools, community colleges, universities, employers, and most recently, community agencies like Boys and Girls Clubs.

Creating the pathways

To create the career pathways, members of the partnership started by looking at data, specifically projections for sustainable wage jobs in the northeast region over the next 10 years.

“They started with the data,” Bragg said, “… because you can’t keep people in these rural counties if they’re not making a living.”

They then met with employers and asked them what they needed to support jobs in those fields. From there, representatives from the various districts’ Career and Technical Education (CTE) divisions, community colleges, and universities worked to build out career pathways for the region, starting with health care.

Building on the enthusiasm for this model across the state, the Department of Commerce, DPI, and the community college system partnered to develop the NCWorks Certified Career Pathways program. The northeast region’s health care pathway became the state’s first certified career pathway in 2016.

The northeast region now has four certified pathways: health care, advanced manufacturing, business services support, and agriscience biotechnology.

A closer look at the Career Pathways model

Since the pilot project in 2013, NENC Career Pathways has gone through changes in both governance and funding. Originally, the state funded the partnership work through a time-limited federal grant and the three workforce boards in the region served as the lead intermediaries. The workforce boards set up a leadership council made up of representatives from each sector to oversee the partnership.

In 2019, the federal grant ran out. At that point, Bragg said, the three workforce boards stepped in to provide the funding for her salary, and the Career and Technical Education departments provide funding for Traitify, a personality assessment tool that helps match interests with careers.

“Everybody tries to put a little bit in — some skin in the game, so to speak,” she said. “Right now, the three workforce boards pitch in, and then most of our CTE departments pitch in … Even our community colleges offer us free meeting space when we could meet in person.”

The pathways are designed to serve everyone from middle and high school students to adult workers who want a career change, Bragg said. “Youth, … adults, even workers over 55, people who have been justice involved, people with disabilities — it’s literally for everyone,” she said.

To measure their impact, they look at a number of factors, including how many students are participating in work-based learning, how many students are graduating from community colleges and universities in the four pathways, and the number of employers engaged with their work. Since 2013, Bragg said they have seen growth in many of these metrics.

Often one of the biggest impacts, Bragg said, is what happens when they get everyone together in the same room.

“When you do things in your little silo for so long, sometimes that’s all you see,” she explained. “And when you can put people in a room together who have different backgrounds and different goals, in some cases, then they’re able to find ways to work together.”

For Lassiter, the pathways help students understand how to get where they want to go. Just as importantly, she said, they also help students understand what they don’t want to do, and what other options are out there. There are so many different roles in health care that unless someone has family involved in the health care system, they may have no idea the different careers out there, she said.

Lessons learned

Bragg explained the biggest lesson they’ve learned throughout this partnership is something their chairman, Walter Dorsey, tells people at every meeting: “Leave your ego at the door.”

“[The partner organizations] all have their goals based on whatever their job is,” Bragg said, “but when we’re coming together like that, we need to be thinking as a community, and that’s what we try to do.”

Collaboration and learning to work together rather than in their own silos has been key to their success, Bragg explained, but it is not without its own challenges.

“I do feel like a cat herder sometimes,” she joked. However, she said they are pretty used to working together in the northeast.

“We don’t have a lot of resources, so we have to work together on things,” Bragg said.

The pandemic has forced the partnership to pivot, Bragg said, especially in areas such as job shadowing and work-based learning. They’ve had to move their meetings and events online and are exploring how to do virtual job shadowing to continue exposing students and families to the different jobs in the area.

Before the pandemic, their next area of focus was implementing the career pathways at the local level, Bragg said. “We start with a community college area, and they bring all their local partners that are within that territory together,” she explained. “They look at our regional pathway, and they see what works in their area.”

They are also hoping to expand involvement in the career pathways initiative outside of the Career and Technical Education side of the local school districts.

“Our next hope is to get it to the English teachers and the science teachers and the math teachers — the ones that are touching every kid,” Bragg said.

Behind the Story

Molly Osborne did the reporting and wrote the story. Alli Lindenberg shot the footage and Robert Kinlaw produced the video.

Editor’s note: The article originally said the state stopped funding the grant in 2019. It has been updated to clarify that the state was funding the partnership through a time-limited federal grant that ran out in 2019.