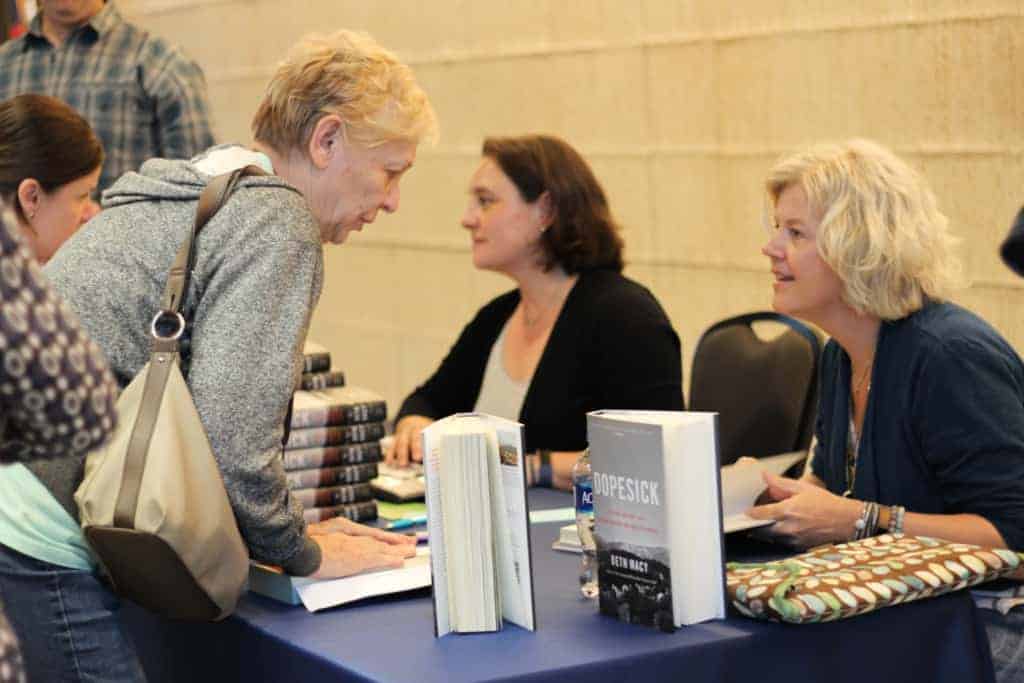

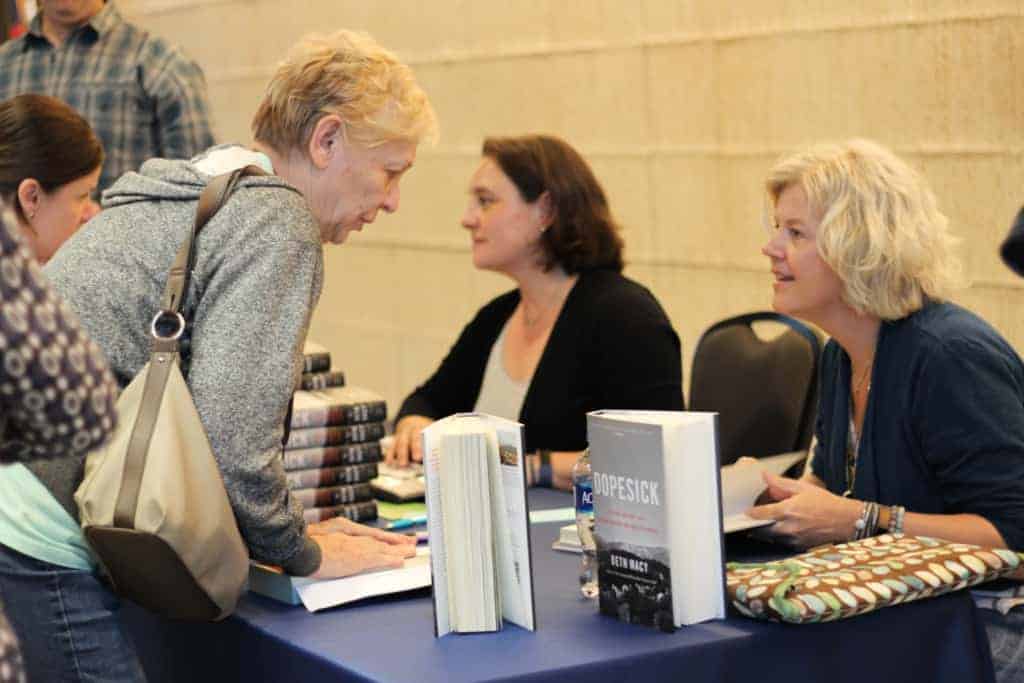

Journalist and bestselling author Beth Macy presented on her book “DOPESICK: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America” on April 24 at Surry Community College (SCC).

“It addresses such a crucial, important, current topic for us,” said David Wright, associate dean for learning resources at SCC, of Macy’s book on the opioid epidemic. “It affects families, it affects our students, it affects all of us.”

Unfortunately, Surry County can relate to the author’s opioid research all too well. According to data from N.C. Injury and Violence Protection Branch, the county experienced the highest rate of opioid overdose emergency department visits in the state in 2017.

The prevalence of the issue even prompted SCC students in the Phi Theta Kappa Honor Society to create a documentary called “The Dark Side of Surry County” highlighting the issue of opioid addiction in their community. However, the opioid issue is far from just a Surry County problem. It’s a nationwide issue that’s no stranger to the headlines, but that wasn’t always the case. Macy — who was a journalist in Roanoke, Virginia — noticed the media, including herself, had been slow to pick up on the epidemic that had taken hold of communities around her.

She was working on another book called Factory Man when she learned that drug-related crime was going through the roof and wrongly assumed people were committing these kinds of crimes, like robbery, to feed their families because of unemployment. She would later find out most people were committing these crimes because they were dopesick — “which they all say is like the worst flu times a hundred,” she said.

The term dopesick describes opioid withdrawal symptoms and would become the title of Macy’s book, which examines the first places opioid addiction began to take root. One character Macy follows in her work is Dr. Art Van Zee of Lee County, Virginia, who had already recognized the problem in his community nearly 20 years ago.

“Art Van Zee saw it unfolding, and he was terrified,” she wrote. “Within two years of the drug’s release, 24 percent of Lee High School juniors reported trying OxyContin, and so had 9 percent of the county’s seventh graders. And Van Zee not only met with worried parents; he’d been called out to the hospitals late at night about the overdose of a teenage girl he’d immunized as a baby.”

Macy said part of the reason it took so long for people to pay attention was because the issue started as a rural problem. That location, she said, was also not coincidental. In her talk, Macy pointed out that pharmaceutical companies had a hand in where the epidemic first took hold: Makers of OxyContin would send sales reps to places like Mount Airy, where there were workplace injuries, and where they knew doctors would already be prescribing pain medication. Representatives would even receive bonuses for promoting higher doses.

Until recently, pharmaceutical companies largely operated using these tactics with little consequence. But as of late last year, 1,400 local governments had filed lawsuits against opioid manufacturers, meaning news of more charges are likely still to come. Just last month, federal criminal charges were brought against Rochester Drug Cooperative over the opioid crisis in the first of such charges against a pharmaceutical distributor. In April, opioid maker Indivior faced charges for fraudulent marketing — the company had misled doctors on their drugs’ potential for abuse. And in March, OxyContin maker Purdue Pharma settled with the state of Oklahoma for $270 million.

If the settlement amount is any indication, the opioid crisis has proved to be a pervasive and costly issue for communities across the country.

“The fear of being dopesick portended one hell of a business model,” Macy said of the epidemic that has resulted in over 200,000 opioid overdose deaths in the nation since 1999, with no end in sight. She cited research that surmised that another 300,000 people will die from drug (not limited to opioid) overdose in the next five years. And according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, more than 130 people are dying specifically due to opioid overdose each day.

Through her book, Macy devoted herself to learning about the people behind these statistics. There was Tess Henry from Roanoke, who received an opioid prescription after a case of bronchitis. She was hooked, and the pain killer addiction would turn into a heroin addiction. The habit would land her in jail at five months pregnant, a pregnancy she hadn’t been aware of.

She would later lose custody of her son (which also meant losing Medicaid coverage), become homeless, and turn to prostitution in Las Vegas, where her family sent her for rehab. In rehab programs, she was often denied M.A.T. — medication-assisted treatment — and turned back to heroin. She remained homeless in Las Vegas for most of 2017, using and dealing drugs.

On Christmas Eve that year, her body was found in a dumpster. She had died from blunt trauma to the head, and the case of her murder remains unsolved. She was 28 years old.

In an opinion piece for the New York Times, Macy described how Henry repeatedly fell through the cracks of a broken treatment system and a community that wasn’t prepared to save her.

“Tess’s quest for treatment had lasted six years, during which time she was repeatedly left to fend for herself by the police, the medical community, the state legislators who refused to expand lifesaving access to Medicaid, weary family members and treatment advocates urging abstinence and tough love and, once, when she begged me to pick her up from a drug house — and I declined — by me,” she wrote.

“The horse is out of the barn. The genie’s out of the bottle. What are we going to do?” Macy asked the audience at SCC. As a journalist, she explained, she was supposed to give both sides, but after having visited family funerals due to opioid-related overdoses, she said her perspective has changed.

“Guess what? I don’t do that anymore,” she said. “I’m done giving both sides. I have opinions.”

Macy emphasized that Henry was trying to get help. She had made plans to come back to Roanoke. She wanted to be reunited with her son. But Macy said she knew anyone in recovery from opioid addiction had a long road ahead of them: it takes eight years and four to five treatment attempts to achieve one year of sobriety.

“In the era of fentanyl, we don’t have eight years,” Macy said, referencing the synthetic opioid with a potency up to 100 times stronger than morphine — a drug that agencies are familiar with in Surry County.

“Heroin is big here. Fentanyl’s come now. Carfentanil’s here,” said John Shelton, Surry County emergency services director, in follow up to Macy’s talk. Carfentanil is a synthetic opioid with a potency 10,000 times stronger than morphine.

“What I can assure you of though is that all of our agencies are working together to combat this problem,” Shelton said. “All of them.”

In Surry County, agencies have broken out of silos to work together, including hospitals, the sheriff’s office and other law enforcement agencies, other health service providers, school systems, and social services.

The collaboration is having some success. After 55 overdose deaths in 2017, Shelton said the county saw 32 last year. This year, the county has had 7 overdose deaths so far.

“The decline in that is Narcan,” Shelton said, referring to a medication (naloxone) that can reverse opioid overdose, which all of the law enforcement agencies in the county now use.

But while Narcan may be saving people from overdose deaths, many remain addicted.

“We’ve got individuals out here that we have resuscitated from cardiac arrest eight times,” Shelton said. “That monkey on their back is so strong, they just can’t let go of it.”

This is where treatment services, like those provided at Daymark Recovery, come in.

“Over the last year and half we have seen more growth on the recovery and treatment side of Surry County than in all the years combined that I’ve been in practice, which is around 20,” Daymark’s Emily McPeak said.

Although the center provides M.A.T., McPeak says the center could serve three times the number of people it’s currently serving.

“I’ll paint no pretty picture here, I couldn’t if I wanted to, but we’re not where we need to be,” she said. Still, McPeak remained hopeful about lives changing dramatically through treatment and recovery and said a drug court was in the process of being developed in the county.

“Treatment works. Recovery works. We get to see those stories day in and day out,” she said.

Unfortunately for hundreds of thousands of people across the country, the right services weren’t provided in time. Macy dedicated her book in memory of 12 of those people, including Henry. She closed her talk by showing the necklace she wore — a gift from Henry’s mother. It included an excerpt from a poem by E.E. Cummings: i carry your heart with me (i carry it in my heart).

Engraved on the other side of the necklace, a quote from James Baldwin:

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”