BOSTON: A Best Practice Example

Boston boasts the fourth-highest number of colleges among all American cities. With its large student population, Boston has pioneered strategies to promote the quality and quantity of student housing while also relieving pressure from the city’s rental market.

Background

Boston addressed student housing in its “Housing a Changing City: Boston 2030” initiative in recognition of the challenges that its more than 159,000 post-secondary students face when searching for housing, as well as their impact on the overall housing market. In this initiative, the city outlines actions aimed at improving the quality and quantity of housing for Boston higher education students with the overarching goal of relieving pressure from the city’s rental housing market. The plan introduced three principal goals, updated in 2018, to be achieved by 2030.

- Reduce the number of students living off-campus in Boston by 50%, to less than 12,000 undergraduate students.

- Create 18,500 new student housing dorm beds.

- Improve living conditions for off campus students

In the ten years since this program’s conception, Boston has employed different strategies in collaboration with higher education institutions to meet these goals.

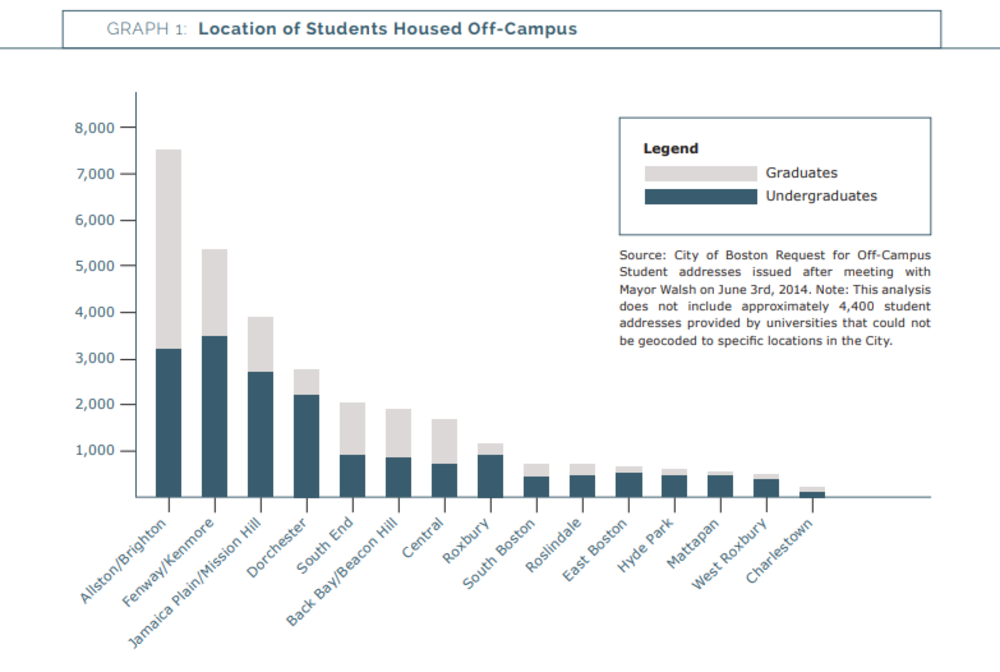

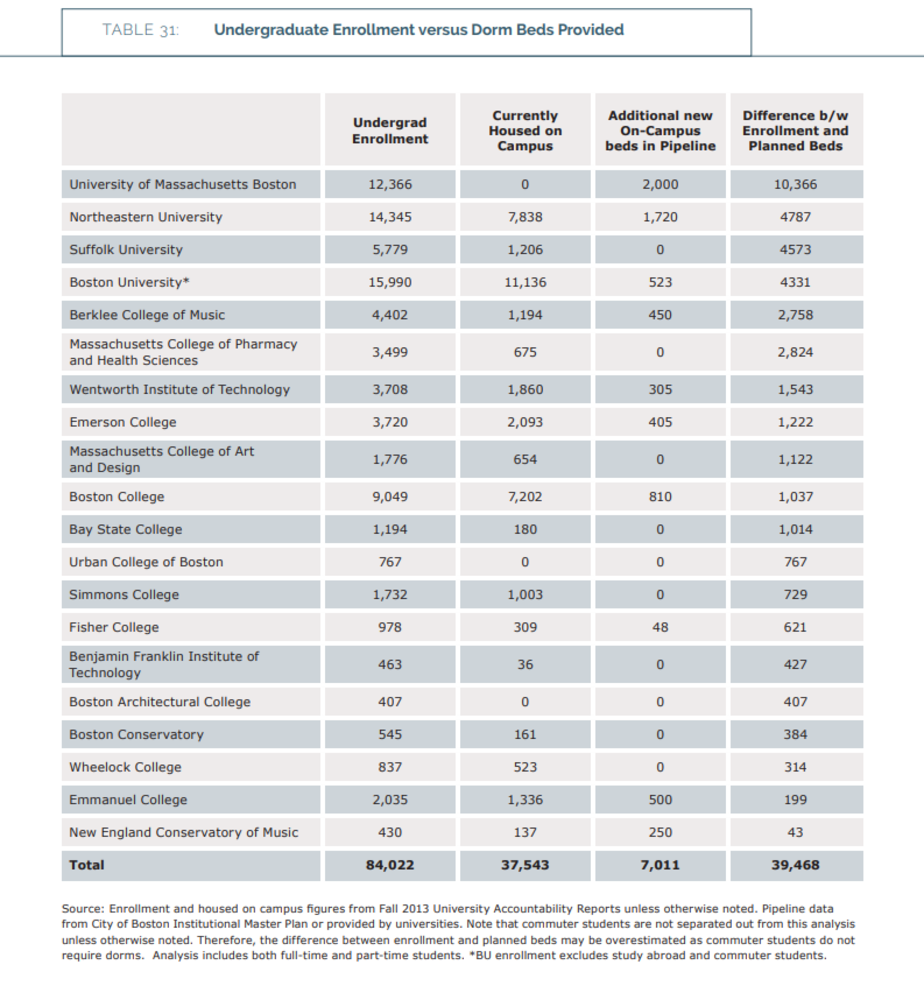

Strategy: Increase institution responsibility

During the summer of 2014, the Mayor and City Council passed and signed into law the University Accountability Ordinance. This ordinance requires that Boston’s colleges and universities report their enrollment numbers and the living arrangements of their undergraduate and graduate students, including the exact addresses of off-campus student residences. Since 2015, the City has produced an annual report on the findings and trends identified in the collected data. The reports assist in tracking the efforts and progress towards fulfilling the production goals of the initiative. Requiring universities to report data also functions as an accountability mechanism, encouraging institutions to confront their housing market impacts and to alleviate their effects through the creation of more student housing. One limitation of the ordinance is that it excludes community colleges from its data collection. Though community college students do not have the same housing needs as traditional 4-year college students, they still face similar challenges in securing housing. Without these students included, the reports do not provide a full picture of the student housing situation.

The University Accountability Ordinance helps increase the transparency of the student housing aspect of Boston’s “Housing A Changing City: Boston 2030” initiative. Similar ordinances that require regular updates on student housing data can help cities track the progress of their efforts and promote institutional accountability for the creation of additional student housing.

Examples of Requested Data in Boston's University Accountability Ordinance

Figure from Boston's: Housing a Changing City Report 2030

]Examples of Requested Data in Boston's University Accountability Ordinance

Figure from Boston's: Housing a Changing City Report 2030

Strategy: Public-private partnerships

In its Housing 2030 initiative Boston identified public-private partnerships (P3s) as an innovative approach to unlock faster production of student housing. While student housing must compete with other institution priorities for capital dollars, like the construction of new instructional space or science labs, private partners defray project costs and offer more financial flexibility. They also minimize the debt load and distribute the risk of new developments across multiple partners. To help facilitate these partnerships, Boston organized exploratory sessions to connect institutions to developers and identify potential barriers to co-development (Walsh 2014).

Leveraging private developers’ expanded interest in student housing, Northeastern University partnered with American Campus Communities to develop and operate Lightview, its newest student residence. The development offers 825 beds at more affordable rates than other housing options close to campus. Though Lightview is private housing, it imitates on-campus residences by offering amenities catered for students, such as study spaces and an Academic Success Center. This public-private partnership was spearheaded by the City of Boston and allowed Northeastern to expand its student housing without using its own funds. Public-private partnerships can be successful on campus as well. In 2018, the University of Massachusetts Boston opened its first on-campus dormitory which was both financed and developed by Capstone Development Partners. The project doesn’t utilize any state funds or student fees to cover its costs, keeping housing and dining access affordable for its more than 1,000 residents.

Photo of the Lightview from American Campus Communities' Lightview website

However, P3s also bring their own set of complexities. Private developers and education institutions have different interests: while developers are searching for a profitable deal, schools aim for affordable housing for students. Therefore, institutions must select partners who prioritize student wellbeing or run the risk of creating housing with the rates and challenges as non-university affiliated options. Additionally, one barrier private developers face in the creation of student housing is community opposition. While large scale student housing is needed to effectively relieve pressure from the rental market, residents near proposed developments are often concerned with student behavior, loss of the character of the neighborhood, and over-crowding. Strong public pushback in Boston has delayed and even barred student housing projects. So, when planning for student housing, city offices should play a mediating role between private developers and communities when selecting viable locations for student housing.

Boston demonstrates how public-private partnerships can be used to increase institutions’ housing capabilities and help free up housing needed for the local workforce. This model is effective and easily replicable for other cities seeking to expand student housing at a minimal cost. Cities should be aware of the potential for local opposition and work to alleviate those concerns and support solutions acceptable to both developers and communities.

Strategy: Implement creative programming

In 2017, Boston introduced the Intergenerational Homeshare program which pairs elderly adults with graduate students searching for housing. Homesharing offers an affordable alternative to the private market for graduate students--the average rent was only $700 and some guests saved additional funds by assisting with basic chores. This program serves the needs of both participants: the student renter can off-set higher rental costs while the older host is able to stay in their home through additional income and increased social interaction. By residing in units already off-the-market, students secure affordable housing and effectively free-up units for Boston's workforce that the students would have otherwise occupied.

"I like being able to feel as though I'm helping in another way. His PhD program might have been a reach if he had to pay for a room alone, but now there is another alternative" -Host

While the pilot program only matched 8 pairs, there has been significant interest and Boston is seeking to expand Intergenerational Homeshare to 100 pairs. Homesharing is an innovative and viable program that other cities could adopt to increase housing affordability for both seniors and students as well as relieve pressure from the general rental market.

Strategy: Establish routine proactive inspections of all off-campus student housing

As part of its student housing initiative, Boston committed to using all its tools to enforce housing codes to ensure safe living spaces for students. In 2013, Boston enacted an ordinance that mandates the inspection of all rental units at least once every five years. Student housing units, which often suffer from substandard conditions and suspected overcrowding, will be prioritized in the ordinance’s mandated inspection efforts.. To expand inspection efforts, city inspectors are stationed in high student volume neighborhoods during move-in weekends where they search for any code violations and conduct on-site reviews upon tenant request. If problems are encountered, landlords are fined and given a chance to remedy the issue. However, if the living situation is not improved, the student tenants will be assisted by the City to relocate them to alternative housing, owned by their current landlord or their university. This outreach can help inform students of their rights as tenants and potential housing hazards.

While increased efforts to enforce code can promote safer living conditions for students, Boston’s capacity to implement these efforts are limited. The code enforcement agency does not have enough inspectors to meet the flood of complaints and routinely inspect rental units every five years. As a result, many student units continue to deteriorate and exacerbate the already substandard living conditions. Other cities can also prioritize code enforcement in off-campus housing to promote student safety. However, they must be prepared to increase the budget and staff of their enforcement agency. Without being paired with resources to increase capacity, these efforts are largely ineffective. Additionally, there is the potential risk of racial and economic bias emerging in code enforcement. A Boston research paper found that city responses to code complaints were “slower, more frequently overdue, and less likely to result in a repair, in both racially diverse and low-income neighborhoods of Boston” (Lemire 2022). This study exposes the ways that code enforcement may not be adequate in equally protecting all students from substandard living conditions. To alleviate this bias when monitoring student housing, cities may consider dedicating additional resources to responding to under-enforced areas and offering inspectors equity trainings.

Strategy: Improve communication with students about housing conditions

To increase the transparency around housing conditions, Boston launched a RentSmart website, which allows potential tenants to view all the housing and service complaints filed for a property in the past five years. Users only need to enter an address to access a property or unit’s data, as pulled from the city’s Inspectional Services Department. While the RentSmart was created to serve students, it is available to any resident. The tool can help students, who are particularly vulnerable to unsafe living conditions, make informed decisions about the properties they’re considering renting. One weakness, however, is the absence of the complaint’s status—whether it was resolved or when, or if the complaint was found to be valid. However, the site is effective at identifying repeat offenders to potential renters.

Other cities can replicate Boston’s RentSmart website through establishing their own user-friendly platform to increase the accessibility of already existing code complaint and violation data. By adopting a similar tool, cities can empower residents to make informed choices when selecting housing while also promoting a culture of compliance and safety.

Results

Using data from the latest Student Housing Report released in 2022, Boston’s strategies to increase the quantity and safety of student housing has been successful thus far. The updated “Housing A Changing City: Boston 2030” initiative set a goal of creating 18,500 new undergraduate beds. Since 2014, when the plan was implemented, colleges and universities added 6,466 dorm beds with another 2,872 beds in the pipeline. The city has completed 50.5% of its 18,500 bed goal halfway through the timeline. At the time of the plan’s inception, 57% of Greater Boston area undergraduate students lived off campus; 8 years later 49.5% lived off campus. Though this figure is not quite a 50% decrease, Boston has made significant progress in increasing the proportion of students living on-campus. This decrease demonstrates that there has been an increase in on-campus housing available to students—a trend that aligns with the stated goal. Overall, these results suggest that the strategies the city employed to increase student housing has been successful and could possibly be adopted by cities to accomplish similar goals.